In fact I have heaps on the go in this space, but this post focuses on two, one an epic recently published book, the other also epic but published online since 2008 and now hundreds of closely written and meticulously sourced pages.

The first thing to recognise is diversity. As this video — a draft of one intended for the Australian Museum and a young audience — rightly points out, but few Australians really know:

At the level of language groups the country is nowadays quite well mapped, if not totally without disagreement. I am coming to you from Dharawal country, that is from the place south of Sydney down through Wollongong to around Kiama, and out to the west to around Picton. Within that are sub-groups (such as Wodi Wodi around here, and Gweagal around Port Hacking) in no simple system from the European viewpoint — indeed overlays by western observers often lead into traps for the unwary. It is complicated by gender considerations, and the fact that some matters were/are secret. Linguistic anthropologist Patrick McConvell says: “Those who have studied the kinship and social organisation systems of Indigenous Australians have been equally astounded by their crystalline beauty and frustrated by their impenetrable complexity.” (Skin, Kin and Clan, ANU Press 2018.)

Neither of the texts I am introducing here ventures into that space without great care and caution. As Barry Corr notes: “…the impact of Land Rights and Native Title legislation … has turned the identity of Aboriginal people of the Hawkesbury into a battlefield…”

So note too that both texts deal with the river system that virtually encircles Sydney — Dyarrubbin, known to us as the Hawkesbury-Nepean River. One set of its branches begins in the mountains I can see from my window, the Cataract and Cordeaux Rivers. It is the specific histories of all the peoples of that river system that both texts are addressing, not of peoples of other parts of Australia.

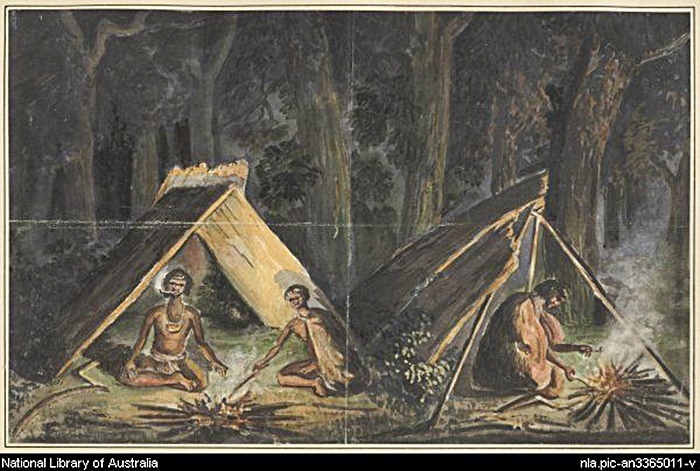

The artworks in this post are of considerable historical interest. They are by William Romaine Govett (1807-1848) after whom Govett’s Leap in the Blue Mountains is named — and no, he did not leap off it as once I used to think!

Yesterday on Facebook I posted my enthusiasm about the first book:

I am half-way through this book now and all I can say it is totally awesome! Paragraph by paragraph comes something I never knew before, a revelation or just an insight. And it is all the people of the river — those there from time immemorial and those who came later. Cliche after cliche is swept away as if by the floods of the Hawkesbury-Nepean itself. That so much of what passes for the right attitudes on our history is actually posturing based on very little real knowledge, on cartoonish goodies and baddies formulae, becomes painfully obvious. Not only am I deepening my knowledge of my own family and the environment they lived and worked in all those years ago, but I am also seeing how history should be done — honestly, frankly, without easy stereotypes. A true history from below, and yes the shades of such as E P Thompson are plain to see — for the good. Everyone should read this book. It is like being connected to the past by 5G when you were up until now on dial-up!

For more depth see: ABC Radio National — Conversations with Richard Feidler where Grace Karskens is interviewed about People of the River.

Her 2011 TED talk gives insight into Professor Karskens’s approach to history:

The second item I enthused about lately is an online text, though I have PDF-printed the whole work for ease of use at any time. Here is how I introduced Pondering the Abyss: a study of the language of settlement on the Hawkesbury Nepean Rivers by Barry Corr.

This is historian Barry Corr who was one of the original Freedom Riders here in NSW in the 1960s. He is referred to in Grace Karskens, “People of the River”. Speaking of what happened after the 1816 Appin Massacre, Karskens says: “It was Aboriginal historian Barry Corr who patiently combed official archives and the rich body of local lore, and first revealed the extent of this hidden and terrible campaign.”

His Nangarra website includes his magnum opus. Should you choose to download the full Pondering the Abyss you will have 937 pages of history, documents and discussion.

Pondering the Abyss has been progressively published online since 2008:

because of a personal belief that Aboriginal history should not be a vehicle for profit;

as one small contribution to reducing the amount of paper in circulation;

to provide ease of access for an international audience; to increase access to primary source material available on the Internet;

so that I am not a gatekeeper between knowledge and the reader;

because it is ongoing, recognising the deep divisions that still remain; allowing updates, corrections and the incorporation of constructive criticism; and

because I keep tinkering with it as the mood takes me.

A unique feature which makes this such a treasure-trove is this:

Pondering the Abyss is somewhat unusual in that contains large amounts of primary sources in their entirety. All primary sources in this work are italicised for the aesthetic reason that it is easier to distinguish them from my comment.”Also: “Pondering the Abyss uses the traditional historical tools of gathering and assessing historical documents in addressing the Language of the settlement of the Hawkesbury Nepean Rivers. Pondering the Abyss may take the reader further and deeper into the darkness of the settlement of the Hawkesbury Nepean Rivers and what subsequently rolled out inexorably over much of Australia, than either the ‘blindfold’ or ‘black armband’ sides of the ‘History Wars’.

On what I have read so far I would say this is very true. By “the Language of the settlement” he means the very discourse through which events have been framed by participants and those who have come after. This is not just some pomo thing — it is often extremely enlightening.