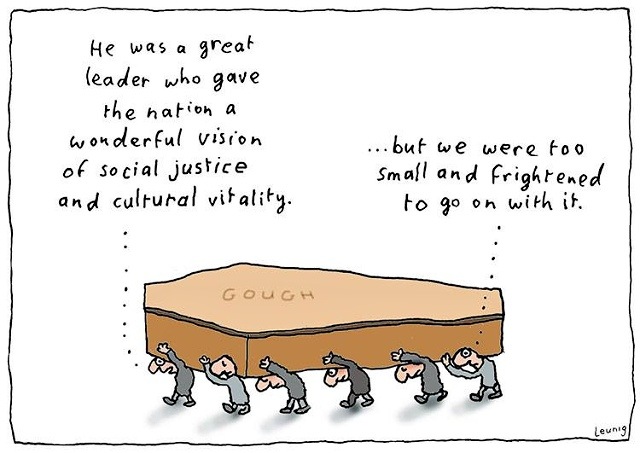

But first Leunig’s take on the passing of EGW:

If that were an HSC question I guess we would add: DISCUSS.

Last night I posted on Facebook: “The entire Whitlam period coincided pretty much with my working at TIGS, with the denouement happening in my first year at Wollongong High. It’s like part of my own life has died today in a way…” Also: “Great to see all Parliament rising to the occasion today in the Condolence Debate.”

Someone I taught at TIGS 1971-1974 posted: “It has just occurred to me that myself, [x] and many others like us would have accepted our scholarship and been teachers because our parents could not have afforded to pay Uni fees. I believe I owe my professional career for what it is worth to EGW.” He added: “And it has just occurred to me Neil James Whitfield, that I was sitting my HSC English exam when Gough was dismissed. I recall a teacher walked into the room and wrote this on the blackboard. He then turned and walked out. I recall looking up and thinking “what’s going to happen now”…”

I by then was at Wollongong High. I had forgotten that November 11 coincided with HSC English, but I do recall the shock of the Dismissal. There were significant Wollongong connections too. I see this in Whitlam’s first post-Dismissal press conference:

JOURNALIST: Prime Minister, you’d probably agree that you enjoy a fight. Are you looking forward to the election campaign and when will you officially launch the campaign?

WHITLAM: I can’t be sure when I’ll be making my first Public speech but I think I will be having something of political relevance to say at the Liverpool town Hall on Thursday when I’m at the naturalisation and at Wollongong on Saturday night when I’m at a social function then. Certainly I like a fight. I’ve won a fair number of fights and I expect to win this one. I’ve never known so clear cut an issue. It’s not just what happens to my Government, what’s been done to my Government, it’s what can happen to any Government which thereafter is given a majority in the House of Representatives by the electors and which retains that majority in the House of Representatives. Parliamentary democracy is at stake in Australia here….

I didn’t actually watch the special repeat of “Whitlam: The Power and the Passion” on ABC last night – that links to my 2013 post the first time it was shown.

I enjoyed last night’s episode and look forward to next Sunday’s account of the subsequent collapse. It is a dramatic story, no doubt about it. And it was a an exciting time to be young, or young-ish in my case. I was 32 when Gough crashed and burned, and I still remember Rex Connor appearing dramatically at the Wollongong High speech night in, I think, October 1975, rather late — having been held up by events.

If I am correct in that memory then Rex Connor would have been held up because he was being sacked.

During 1974 Connor sought to bypass the usual loan raising processes and raise money in the Middle East through an intermediary, a mysterious Pakistani banker called Tirath Khemlani. Because of strong opposition from the Treasury and the Attorney-General’s Department about the legality of the loan (and about Khemlani’s general bona fides), Cabinet decided in May 1975 that only the Treasurer, not Connor, was authorised to negotiate foreign loans in the name of the Australian government. Nevertheless, Connor went on negotiating through Khemlani for a huge petrodollar loan for his various development projects, confident that if he succeeded no-one would blame him, and if he failed no-one would know.

Unfortunately for Connor, Khemlani proved to be a false friend and sold the story of Connor’s activities to the Liberal Opposition for a sum which has never been disclosed. Connor denied the Liberals’ accusations, both to Whitlam personally and to Parliament. When the Liberal Deputy Leader, Phillip Lynch tabled letters from Connor to Khemlani, Connor was forced in October to resign in disgrace. The Opposition proclaimed the Loans Affair a “reprehensible circumstance”, which justified the blocking of supply in the Senate, leading to the dismissal of the Whitlam government a few weeks later by Governor-General, Sir John Kerr.

Rex Connor was our local member of parliament.

That Saturday after the Dismissal which Whitlam refers to must have been when I and so many others – colleagues from Wollongong High among them – stood chanting “We want Gough!” at the top of our voices outside Wollongong Town Hall.

See also Whitlam Dismissal site.

Back to the documentary repeated last night:

Troy Brampston does rightly nail a few errors in the documentary, but none of them all that significant aside from the not uncommon trope of exaggerating the benighted state of the country in the late 60s and early 70s when, in fact, quite a few of the changes people attribute to Whitlam had already begun. (One thinks of the 1967 referendum on Aboriginal citizenship just for starters.) Hence the headline Hyperbole for true believers, which is somewhat harsher than Brampston’s overall assessment:

Putting aside these flaws for now, it is a rollercoaster ride as viewers relive the razzle and dazzle of Whitlam’s ascendancy and early days of governing followed by the inevitable crash, as dreams collide with inexperience, economic turmoil and political ruthlessness given vice-regal sanction…

The documentary effectively captures Whitlam as a change agent who not only embodied the mood for change in the electorate but also had a plan for where he wanted to take the country in the tumultuous 1960s and 70s.

Howard praises Whitlam’s skills as opposition leader. “I thought he did a tremendous job as the opposition leader and the way in which he welded the party together and repaired a lot of the rifts and campaigned and developed what he called his ‘program’,” Howard says.

After Labor was elected in 1972, Whitlam had himself and his deputy, Lance Barnard, sworn in holding all ministries between them. Whitlam told Hayden, “It was the best government (I) ever had, except it was twice as large as it needed to be.”

The economy would prove to be Whitlam’s Achilles heel. “You will do great things,” Hawke recalls telling Whitlam, “(but) this government will live or die on your economic performance.”

The documentary spans Whitlam’s life. All the core elements are included, from his experience living in the outer suburbs of Sydney to his rise through the Labor Party and term as prime minister…

There are wonderful stories. Howard remembers telling one of his legal partners he was going to work on Billy McMahon’s 1972 campaign. “I don’t mind you doing it,” the partner said, “but you do realise, John, It’s Time.”

Phillip Adams recalls Treasurer Jim Cairns and Junie Morosi rolling around naked on the lawns of Kirribilli House. It is one of several strange scenes dramatised by actors who bear little resemblance to the people they are portraying. Nobody can portray Whitlam on the screen; he is already larger than life….

The documentary is a reminder of a Labor Party that once “dreamed the big dreams”, as Paul Keating used to say, and an inspirational prime minister with the conviction and courage to pursue them, however fatal his blind spots inevitably were.